As someone deeply immersed in the world of finance and accounting, I find the Modigliani-Miller (M&M) Theorem to be one of the most elegant and influential frameworks in corporate finance. Today, I want to explore the M&M Theorem with corporate taxes, a critical extension of the original theory that introduces the real-world implications of taxation on a firm’s capital structure and value. This article will delve into the mathematical foundations, practical applications, and limitations of the theorem, all while keeping the discussion accessible and engaging.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Modigliani-Miller Theorem

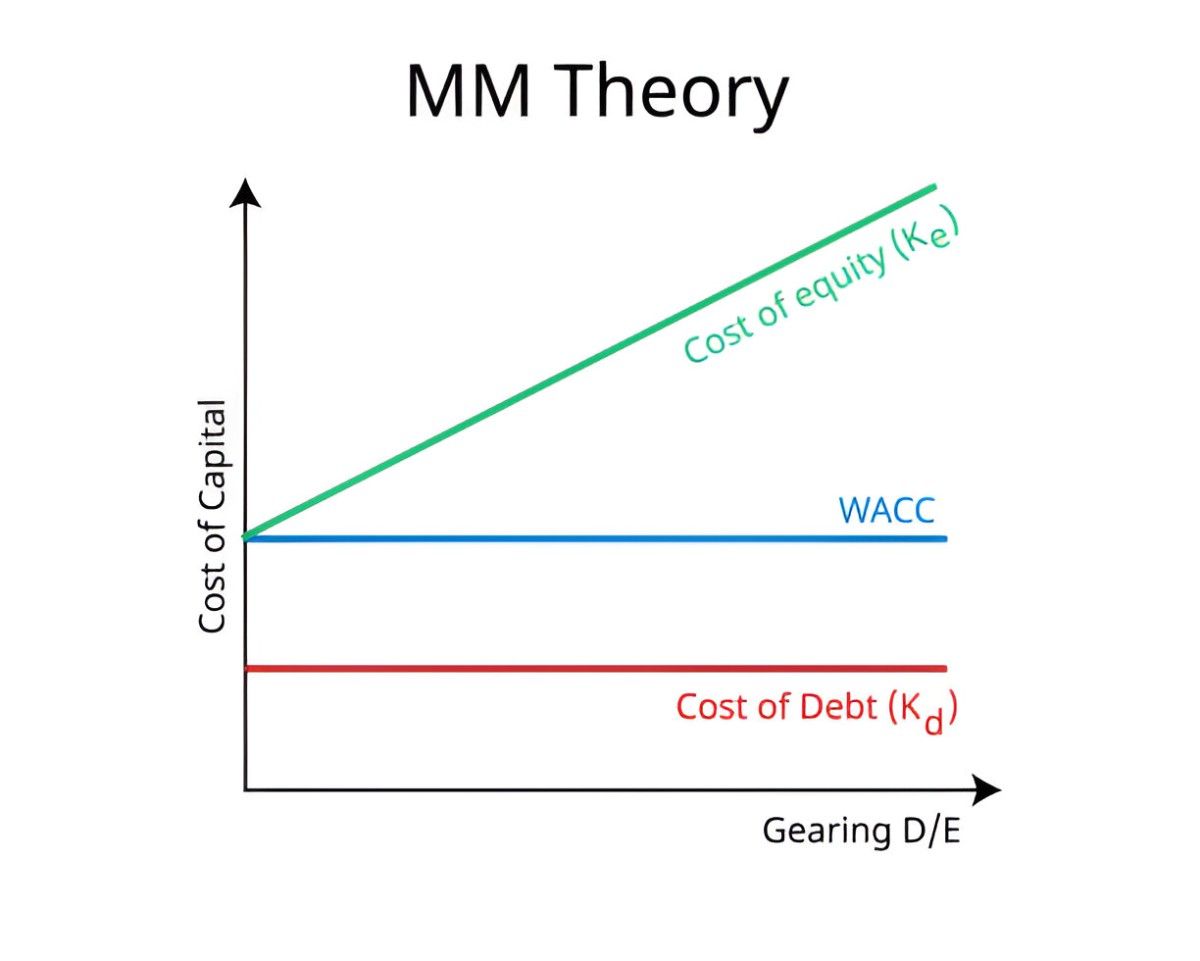

Before diving into the specifics of corporate taxes, let’s revisit the core principles of the M&M Theorem. In 1958, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller published their groundbreaking work, which argued that, under certain assumptions, the value of a firm is independent of its capital structure. In other words, whether a firm finances itself through debt or equity doesn’t affect its overall value.

The original M&M Theorem rests on several key assumptions:

- Perfect capital markets: No transaction costs, no taxes, and no bankruptcy costs.

- Rational investors: Investors behave rationally and have access to the same information.

- No agency costs: Managers act in the best interest of shareholders.

- Homogeneous expectations: All investors have the same expectations about future cash flows.

While these assumptions are elegant, they don’t hold in the real world. This is where the introduction of corporate taxes comes into play.

Introducing Corporate Taxes: The M&M Theorem Revisited

In 1963, Modigliani and Miller revisited their theorem by incorporating corporate taxes. This adjustment fundamentally changes the conclusion: the value of a firm is no longer independent of its capital structure. Instead, debt financing becomes advantageous due to the tax deductibility of interest payments.

The Tax Shield Effect

The primary reason debt becomes attractive under corporate taxation is the concept of the tax shield. Interest payments on debt are tax-deductible, which reduces a firm’s taxable income and, consequently, its tax liability. This creates a “shield” that protects some of the firm’s earnings from taxes.

Mathematically, the value of the tax shield (V_{TS}) can be expressed as:

V_{TS} = T_c \times D

where:

- T_c is the corporate tax rate,

- D is the total amount of debt.

This tax shield adds value to the firm, making debt financing more attractive than equity financing.

The Adjusted M&M Proposition I with Taxes

With corporate taxes, the value of a levered firm (V_L) is greater than the value of an unlevered firm (V_U) by the present value of the tax shield:

V_L = V_U + T_c \times DThis equation shows that the value of a firm increases linearly with the amount of debt it employs, thanks to the tax shield.

The Adjusted M&M Proposition II with Taxes

The cost of equity also changes when corporate taxes are introduced. The relationship between the cost of equity (r_E), the cost of debt (r_D), and the overall cost of capital (r_A) is given by:

r_E = r_A + (r_A - r_D) \times \frac{D}{E} \times (1 - T_c)Here, \frac{D}{E} represents the debt-to-equity ratio. This equation shows that as a firm takes on more debt, its cost of equity increases, but the overall cost of capital decreases due to the tax shield.

Practical Implications of the M&M Theorem with Corporate Taxes

The introduction of corporate taxes into the M&M framework has profound implications for how firms structure their financing. Let’s explore some of these implications in detail.

1. The Optimal Capital Structure

In the presence of corporate taxes, the M&M Theorem suggests that firms should maximize their use of debt to take full advantage of the tax shield. This implies that the optimal capital structure is one with 100% debt.

However, this conclusion doesn’t align with real-world observations, where firms rarely employ 100% debt. This discrepancy arises because the M&M Theorem with taxes still ignores other critical factors, such as bankruptcy costs and agency costs.

2. The Trade-Off Theory

The trade-off theory builds on the M&M Theorem by incorporating the costs of financial distress. While debt provides a tax shield, it also increases the risk of bankruptcy. Firms must balance the benefits of the tax shield against the potential costs of financial distress.

Mathematically, the value of a levered firm under the trade-off theory can be expressed as:

V_L = V_U + T_c \times D - PV(\text{Financial Distress Costs})This equation shows that the value of a firm increases with debt up to a certain point, after which the costs of financial distress outweigh the benefits of the tax shield.

3. The Impact on Firm Valuation

The M&M Theorem with corporate taxes provides a useful framework for valuing firms. By incorporating the tax shield into the valuation process, analysts can more accurately estimate a firm’s value.

For example, consider a firm with the following characteristics:

- Unlevered value (V_U) = $10 million

- Corporate tax rate (T_c) = 30%

- Debt (D) = $4 million

Using the adjusted M&M Proposition I, the value of the levered firm is:

V_L = 10 + 0.3 \times 4 = 11.2 \text{ million}This simple calculation shows how the tax shield adds $1.2 million to the firm’s value.

Limitations of the M&M Theorem with Corporate Taxes

While the M&M Theorem with corporate taxes provides valuable insights, it has several limitations that must be acknowledged.

1. Ignoring Bankruptcy Costs

The M&M Theorem with taxes assumes that bankruptcy costs are negligible. In reality, financial distress can lead to significant costs, such as legal fees, lost sales, and reduced employee morale. These costs can offset the benefits of the tax shield, making excessive debt financing risky.

2. Agency Costs

The theorem also ignores agency costs, which arise from conflicts of interest between managers, shareholders, and debt holders. For example, managers may take excessive risks to benefit shareholders at the expense of debt holders, leading to higher borrowing costs.

3. Personal Taxes

The M&M Theorem with corporate taxes focuses solely on corporate taxation. However, personal taxes on interest income and dividends can also influence a firm’s capital structure decisions. For instance, if interest income is taxed more heavily than dividends, investors may prefer equity financing over debt financing.

4. Market Imperfections

The theorem assumes perfect capital markets, which don’t exist in the real world. Factors such as transaction costs, asymmetric information, and market frictions can all impact a firm’s financing decisions.

Real-World Applications and Examples

To better understand the M&M Theorem with corporate taxes, let’s look at some real-world applications and examples.

Example 1: Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

Leveraged buyouts are a classic example of the M&M Theorem in action. In an LBO, a firm is acquired using a significant amount of debt, which creates a large tax shield. This tax shield increases the value of the firm, making the acquisition more attractive.

For instance, consider a firm with an unlevered value of $50 million and a corporate tax rate of 25%. If the acquiring firm uses $30 million in debt to finance the acquisition, the value of the levered firm is:

V_L = 50 + 0.25 \times 30 = 57.5 \text{ million}The tax shield adds $7.5 million to the firm’s value, making the LBO financially viable.

Example 2: Capital Structure Decisions

The M&M Theorem with corporate taxes can also guide firms in making capital structure decisions. For example, a firm with a high tax rate may choose to increase its debt levels to maximize the tax shield. Conversely, a firm with a low tax rate may prefer equity financing to avoid the risks associated with debt.

Conclusion

The Modigliani-Miller Theorem with corporate taxes is a cornerstone of modern corporate finance. By introducing the concept of the tax shield, it provides a compelling argument for the use of debt financing. However, the theorem’s assumptions limit its applicability in the real world, where factors such as bankruptcy costs, agency costs, and personal taxes play a significant role.